Charles of London

Charles of London, working closely with architects Walker and Gillette, supplied more than 400 decorative art objects, including tapestries, tables, chairs, cupboards, beds, and even china and linens to Coe Hall. About 80% of the antique and modern furnishings came from Charles of London at a cost of about $450,000 (about $6 million today.) The rest of the furnishings came from other prominent firms, including Partridge, Stair & Andrews and Lenygon & Morant. Very little of the furniture was antique but was made to look old. As the rooms were finished, they were photographed from 1921 to 1928 by Mattie Edwards Hewitt, who specialized in record photographs for architects and interior designers in and around New York. Her photographs of Coe Hall are in the Planting Fields Foundation Archives.

After Mr. Coe’s death in 1955, virtually all of the furnishings left the house, either inherited by his children and grandchildren or sold at auction. Through 1970, the State University of New York’s college of science and engineering used the house for teaching and research. In the 1970s, the Planting Fields Foundation established Coe Hall as a house museum with ongoing restoration work. About 80 artifacts have been returned from Coe descendants. Through gifts and purchases, additional furnishings in the styles of the originals have been added to the house, thus restoring more rooms to their period glory. In 2015, Mr. Coe’s bedroom, originally furnished by Charles of London, was refurbished based on Hewitt photos from the 1920s. Only two original artifacts from the room survive: a table lamp and the mirror over the fireplace.

Elsie de Wolfe

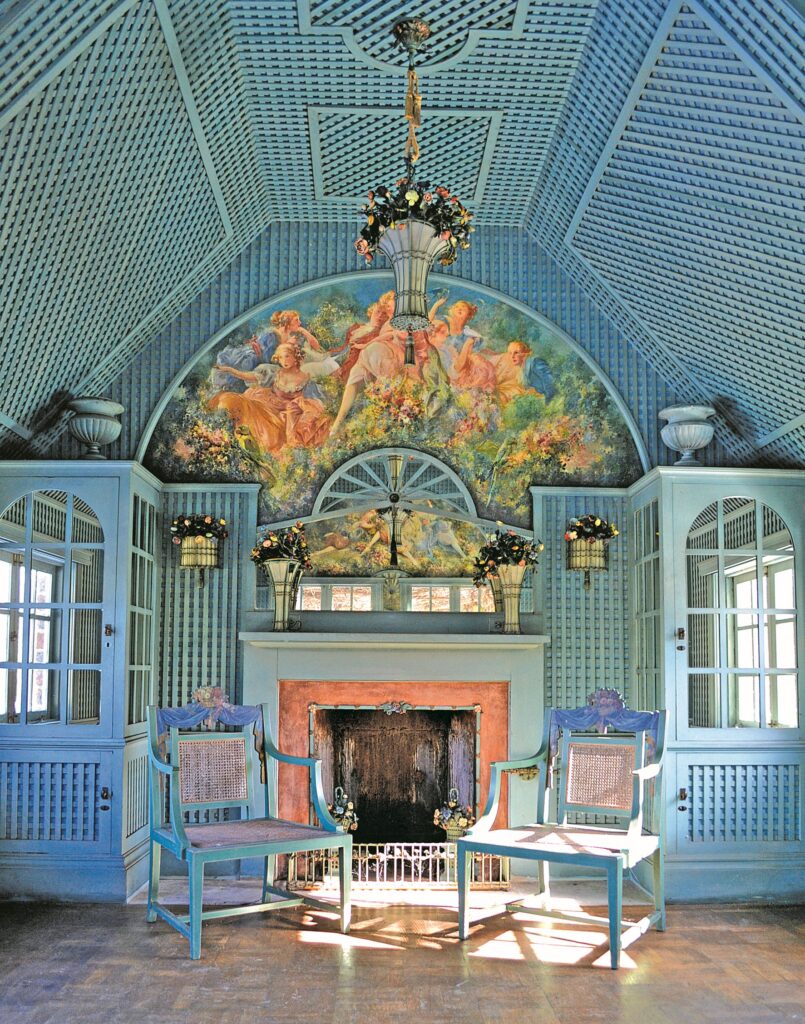

Elsie de Wolfe, one of the most influential female American interior designers of her time, played an important role in the decoration and design of spaces within and around Coe Hall. Most notable is her work in the 1915 Teahouse in the Italian Garden, though her work is also evident in the Reception Room as well as Mai Coe’s and W.R. Coe’s dressing rooms. With its painted trellis ceiling, murals, painted furniture by Everett Shinn and original painted metal light fixtures, the Teahouse is representative of de Wolfe’s French eighteenth century revival style. French designers made the style popular in fine garden rooms in the 1750s and it was de Wolfe who brought the style to America, beginning about 1910. Despite its small scale, it is one of Planting Fields’ greatest treasures.

French Rococo-style murals, signed and dated in 1915 by Shinn, glow with brilliant colors against the blue-green trellis ceiling. A notable painter, illustrator, designer and playwright out of the Ashcan School, Shinn was hired by de Wolfe to paint murals for several private commissions in and around New York City. None apart from this Teahouse are intact. Also surviving in the Teahouse are six ornamental wrought-iron electric light fixtures, crafted to resemble bouquets of flowers and painted in naturalistic floral colors, all part of de Wolfe’s design. They evoke the famous Sèvres porcelain flowers made in the 1760s for Madame de Pompadour, mistress of French king Louis XV.

In 1921, when de Wolfe worked on the design of W.R. Coe’s and Mai Coe’s dressing rooms the latter was also fitted with painted decorative panels by Everett Shinn. These rooms have recently been restored, thanks to the Gerry Charitable Trust. Very little of Elsie de Wolfe’s design work survives anywhere in Europe or the U.S. today.

Interior of the 1915 Teahouse at Planting Fields.