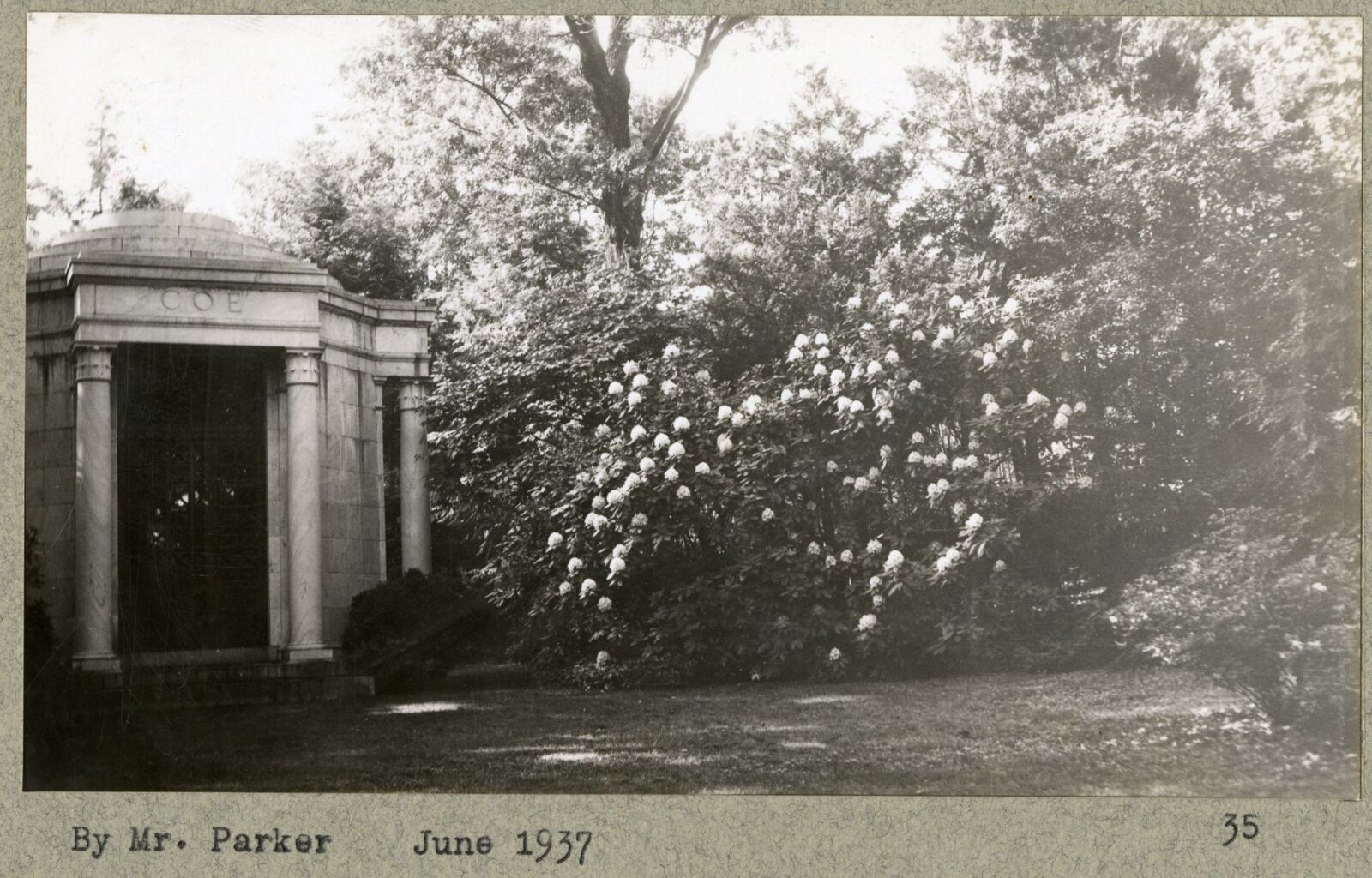

It’s October, so this month’s feature will take a trip to St. John’s Memorial Cemetery where several members of the Coe family were laid to eternal rest, interred in the family mausoleum built in 1927 at the Laurel Hollow cemetery. Architects Walker & Gillette, who designed the Coe residence at Planting Fields, also designed the mausoleum, and the Olmsted Brothers firm created the landscape surrounding their allotment, continuing the working partnership that started on the Planting Fields country estate a few miles away.

Designing burial grounds was not a new venture for the Olmsted firm. Frederick Law Olmsted, founder of the firm his sons would go on to run, was an influential thinker in the “Rural Cemetery Movement” of the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, a school of thought that solved the growing connected problems of exploding city population growth and overcrowded graveyards by reimagining shared burial sites as places of “dignity and tranquility.”

The idea of the “rural cemetery” originated at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1831 with the establishment of Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. Before Mount Auburn, grave sites in America could be one of two options: utilitarian public graves or family plots on private land. In either instance, the grave site was considered an “unattractive necessity to be avoided as much as possible by the living” (French). The rural cemetery was a new kind of place, “’rural’ yet urban, natural yet designed, artistic yet industrial, commemorating the dead yet used by the living” (Smith). Sites like Mount Auburn became the forerunners of the grand public parks that Olmsted would famously design later in the nineteenth century and inspired many iterations across America, including Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn (1838) and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia (1836).

Rural cemetery design, with its emphasis on beautiful foliage, gentle grading, and natural water features, directly engaged with and influenced “the tradition of naturalistic landscape design that was developed by Olmsted” (NPS). Cemeteries would become a sizable portion of their commissioned design work, and many of their residential landscape clients also contracted the Olmsted Brothers to design family plots within larger cemeteries. In the Memorial Cemetery of St. John’s Church where the Coes family mausoleum was built in 1927, for example, the Olmsted effect is compounded: prominent families rest in individual Olmsted-designed plots, but the entire cemetery itself is an Olmsted Brothers creation as well. A peaceful place for New York’s wealthiest families and their descendants to reside forever, and somewhere you can still visit today.

Caitlin Colban-Waldron, Michael D. Coe Archivist

References:

Bender, T. (1974). The “Rural” Cemetery Movement: Urban Travail and the Appeal of Nature. The New England Quarterly, 47(2), 196–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/364085

French, S. (1974). The Cemetery as Cultural Institution: The Establishment of Mount Auburn and the “Rural Cemetery” Movement. American Quarterly, 26(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711566

National Parks Service (NPS) (1981). National Register Bulletin 41.

Smith, J. (2017). The rural cemetery movement: places of paradox in nineteenth-century America. Lexington Books.