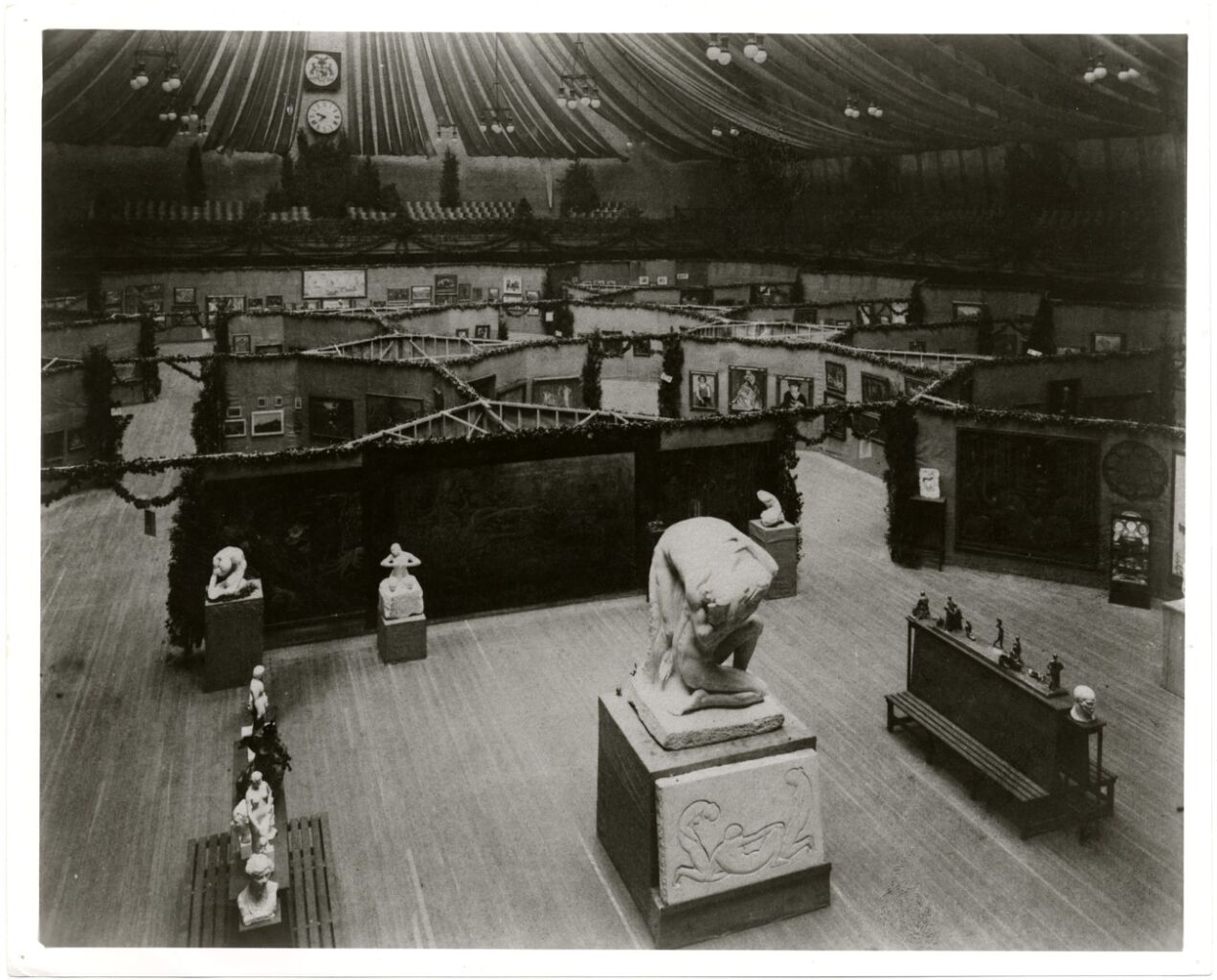

Most art historical accounts credit New York’s legendary 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art—better known as the Armory Show—with bringing European modernism to the American public and indelibly changing the course of Western art history: initiating the shift of the capital of the “art world” from nineteenth-century Paris to twentieth-century New York. Indeed, the Armory Show introduced many Americans to radical, new forms of art by such now-famous men as Cézanne, Duchamp, Gauguin, van Gogh, Hopper, Kandinsky, Matisse, Picasso, and Whistler. It was, by all accounts, a monumental exhibition: held between February 17th and March 15th, it presented around 1300 works by some 300 artists. While many of its male artists have become household names, the Armory Show could never have taken place without the support and participation of nearly one hundred women as financial supporters, collectors, and artists. While we cannot know for certain if Mai Coe visited the Armory Show, we do know that like the women recorded as Armory Show benefactors, including Mrs. Coe’s Long Island neighbors Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and her sister-in-law Dorothy Whitney Straight, Mrs. Coe served as an important champion of American modern art.

While their historical contributions have often been overlooked, Mai Coe and other American women were the first to embrace this new aesthetic vanguard. In the first few decades of the twentieth century, women became major collectors of modern art in their own right and founded three of New York City’s major modern art museums—MoMA, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim. Writing in Vogue in 1940, art and theater critic Frank Crowninshield acknowledged, “it has been the women who have always accorded the modern movement its earliest recognition and patronage.”[1] It is surely no coincidence, then, that of the four murals commissioned by W.R. and Mai Coe for their home at Planting Fields, three of them were for spaces primarily intended for Mai’s enjoyment. Robert Winthrop Chanler, who exhibited numerous of his lavish, dynamic painted screens in the 1913 Armory Show and whose sister was one of its benefactors, created not only the famous Buffalo Mural for Coe Hall’s Breakfast Room but also the original immersive Lace Room mural in Mai Coe’s bedroom, with its tropical botanicals, exotic birds, and lace motif stretching up from the floor to cover the ceiling. In 1915 and again in 1920, the Coes engaged Everett Shinn, a well-known modern painter and member of the Eight, whose 1908 independent exhibition was organized in opposition to the National Academy of Design, New York’s gatekeeping art organization, and as such, served as a predecessor to the revolutionary 1913 Armory Show. At Planting Fields in 1915, Shinn created a turquoise trellised retreat: Mai Coe’s Teahouse in the Italian Garden is filled with a suite of furniture and fittings designed by Shinn with floral motifs and two painted lunettes of lounging women and brightly feathered birds. (In honor of his benefactor, Shinn nestled a silhouette of Mrs. Coe among the painted foliage on the Teahouse settee.) The paintings commissioned from Shinn for Mai Coe’s dressing room five years later are similarly fanciful, with their theatrical scenes of eighteenth-century couples frolicking through an imagined French countryside. As a patron of modern art, actively supporting living artists like Chanler and Shinn, Mai Coe and many other women with independent aesthetic taste had, as art historian Wanda Corn wrote, “a powerful and directorial role in the country’s cultural landscape.”[2] They demonstrated a willingness to move beyond the strictures of the Gilded Age and embrace new freedoms that shaped the artistic course of the new century.

Meredith A. Brown

[1] Frank Crowninshield, “The Scandalous Armory Show of 1913,” Vogue (September 15, 1940), p. 115.

[2] Wanda M. Corn, “Art Matronage in Post-Victorian America,” in Cultural Leadership in America: Art Matronage and Patronage(Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1997), p. 23.

Photo: An overhead installation view of Gallery A at the Armory Show, 1913. Walt Kuhn Family papers and Armory Show records, 1859-1984. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution